The ABCs of Voting: 2020 Edition

Confused about voting? Just curious? We’ve compiled an A – Z list of definitions, resources, and deep dives to demystify the voting process. Whether you’re looking for more information about absentee voting or just geeking out about electoral history, we’ve got you covered.

A: Absentee Ballot

Absentee ballots are having a huge year in 2020. Because of the COVID-19 crisis, many states have expanded access to absentee voting—including Alabama. So what is an absentee ballot? Simply put, it’s a ballot completed and typically mailed in advance of an election by a voter who is unable to be present at the polls. If you’re running short on time and don’t think your ballot would arrive on time via the mail, you can also drop off your ballot at your local Absentee Ballot Manager. Thus far, over 100,000 have cast absentee ballots for the 2020 general election! To learn more about the absentee voting process, check out the Alabama Secretary of State website here.

B: Ballot(pedia)

Ballotpedia is a wonderful nonpartisan resource for learning what exactly will be on your ballot this election. You can visit their website to look up your elected officials and learn more about proposed constitutional amendments. If you haven’t seen it yet, here’s a link to the sample ballots for the Nov. 3 election in Alabama, by county.

C: Confidentiality

Did you know it’s illegal to take a selfie in the voting booth in 21 states, including Alabama?

The secret ballot originated after the 1884 presidential election by way of state reforms as a way to avoid voter intimidation and coercion, although some now argue that its use is primarily symbolic. Others argue privacy during voting is essential for democracy.

Related: while the contents of your ballot are private, whether you vote is public record.

D: Deliberation

Public deliberation is one way to practice everyday democracy between elections. When people desire to address an issue they all face – rather than politics or personalities – deliberative conversations can be especially suited for the uncommon and transformative experience of working together across differences. Problems don’t tend to disappear overnight, and so the everyday habit of talking with each other as citizens – not circling issues, but working towards creating solutions we can all live with – often proves to be, simultaneously, one of the most effective and the most accessible approaches to sustainable community development. It may also be uniquely adapted to include those not eligible to vote, whether because they are under 18 or for another reason.

Through our work, the Mathews Center sees that local civic engagement is one way to overcome apathy and find out whether your voice actually does matter in your community.

E: Electoral College

The electoral college is our country’s process for selecting a president. (Read about it in Article II of the Constitution.) One of its original purposes was to ensure that heavily populated states do not skew presidential election results. This process, or “compromise between election of the President by a vote in Congress and the election of the President by a popular vote of qualified citizens,” is part of what distinguishes U.S. government from other democracies or republics. Representation has been a rallying cry since before the Declaration of Independence, and the electoral college is one of the fundamental ways that Americans are represented in the White House. Political parties in each state choose potential electors sometime before the general election; then, after ballots are counted following Election Day, electors are chosen based on who their state’s voters chose. The Electoral College – a total of 538 electors – then cast their votes; they must have a majority of 270 electoral votes to elect the next president. You can learn about the entire process here.

The electoral college has gained fresh attention following the results of the 2016 presidential election, as the most recent example of how U.S. presidencies are not always won by popular vote. (Here’s an explanation from the Washington Post on which candidates would have won the last five presidential races, under slightly different systems.) You can learn how many electoral votes each U.S. state has through 2020, based on the 2010 Census; currently, Alabama has nine votes in the electoral college.

And, of course, a great deal has changed since the 1780s. The Washington Post offers an in-depth analysis of how the electoral college has changed over time, showing over- and under-representation by state from 1960-2016. One question the author raises is whether a state’s electors should be chosen based on the overall state population, or eligible voter population. For a history of the electoral college and a closer look into why and how it was set up, we recommend the nonpartisan podcast Civics 101: Episode 20.

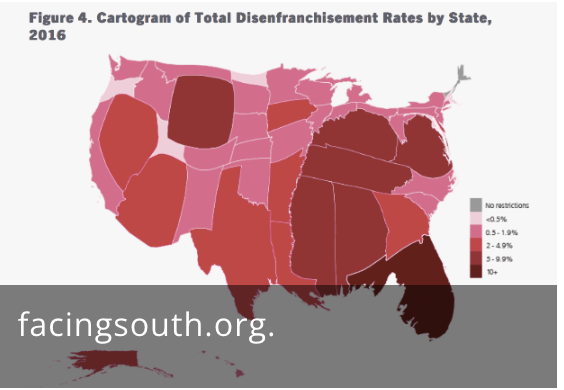

F: Felony Disenfranchisement Laws

Felony disenfranchisement laws restrict the voting rights of Americans convicted of felony-level crimes. While these laws vary by state, the United States is considered to be particularly strict in this area compared to other countries. A complete list of the US. state felon voting laws is available here.)

Last summer Alabama passed a new law, The Definition of Moral Turpitude Act, clarifying which crimes do and do not permanently disenfranchise individuals from their rights to vote. This new clarification means that many previously disenfranchised Alabamians may now seek to restore their voting rights.

The law is considered local progress on an issue that was, in 2016, estimated to disenfranchise up to 6.1 million people nationwide “due to a felony conviction, a figure that has escalated dramatically in recent decades as the population under criminal justice supervision has increased. There were an estimated 1.17 million people disenfranchised in 1976, 3.34 million in 1996, and 5.85 million in 2010.” The Southern Poverty Law Center has created a guide to assist individuals seeking to restore their voting rights.

“[It felt] like it would take a miracle for my rights to be restored and be able to vote again. Now I feel whole again. It means a great deal to me, for the Governor and his administration to do what they did for me and thousands of others. It means they believe in us and the truth that when you pay your debt to society you shouldn’t be punished twice. I will never take this right for granted ever again. They say you never miss something until you lose it.”

-Eric, a Virginia voter whose rights were restored in 2015

Virginia is another Southern state actively seeking to restore voting rights to individuals convicted of a felony “who are no longer incarcerated or under active supervision.” More testimonies of newly enfranchised voters here.

G: Gerrymandering

Every ten years, redistricting occurs in each state’s congressional districts after the national census has been updated. Gerrymandering refers to redistricting with the intent to either reduce or amplify the voting power of a political party. Redistricting is a complicated and bureaucratic process, but for better or for worse, it defines what an electoral district looks like and – as we read with the electoral college – that affects how your vote counts.

Here’s a brief explanation of gerrymandering from FiveThirtyEight, a website whose name is based on the makeup of the electoral college.

With the 2020 Census recently closing, the nonpartisan Brennan Center for Justice is tracking redistricting efforts across the United States.

FiveThirtyEight recently published The Gerrymandering Project, a series aimed at informing its readers what’s at stake and what could be improved. Along with thought pieces and updates by state, the series includes a visual tool called The Atlas of Redistricting. The atlas shows a breakdown of eight different ways that congressional districts could be drawn, illustrating “how changes to district boundaries could radically alter the partisan and racial makeup of the U.S. House — without a single voter moving or switching parties.” The atlas is a helpful visual way to understand the complicated practice of redistricting and its associated benefits and pitfalls.

One of our favorite podcasts, Civics 101, offers a brief nonpartisan explanation of redistricting and gerrymandering, and how it has evolved in the United States.

H: Home Rule

As defined by the Encyclopedia of Alabama, Home Rule “is the power and authority of local governments to run their own affairs. In Alabama, the grant of power is contained in the constitution or is delegated by the legislature by law. Home Rule in Alabama is significantly limited by the state constitution. Counties have no general grant of power in the constitution or from the legislature. Thus counties must go to the legislature for authority to engage in desired activities, either through constitutional amendments which must be initiated by the legislature, or by an act of the legislature (known as “local legislation”) giving the county authority to carry out the desired action.”

Most Alabamians experience the state’s lack of home rule when they go to vote and encounter constitutional amendments on the ballot that are specific to individual communities; this can cause confusion, as voters are curious as to why they are being asked to vote on a measure that affects a particular county or municipality–when they are not residents of said county or municipality. For example, Amendment 482 was voted on by the entire state, passed, and authorized Limestone County “to provide for the disposal of dead farm animals, and the excavating of human graves.”

I: ID

In 2014, Alabama enacted a law requiring voters to present photo identification at the polls. According to the Secretary of State website, “If a voter does not have one of the approved forms of photo ID as stated in the law, then he or she may receive a free Alabama photo voter ID from various locations including the Secretary of State’s Office, local county board of registrars’ offices, and a mobile location to be determined by the Secretary of State’s Office.” Photo ID mobile units may be requested online with two weeks’ notice. The website also provides a 17-page Voter ID guide.

Voter photo ID laws have had controversial reception; its supporters want to re-instill confidence in the election process, and therefore prioritize measures against voter fraud, and its opponents are concerned that such laws present an unnecessary burden on administrations, and that they may disproportionately affect voters who have historically been disenfranchised. Ballotpedia provides a national context with its list of voter identification laws by state; there are 33 other U.S. states with voter I.D. laws. Alabama’s voting laws still receive particular attention given the recent history of the Civil Rights Movement in the South. For more information on voting rights in Alabama today, scroll down to the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

J: Jurisdiction

Jurisdiction simply refers to the area in which you live where you’re registered to vote. However, at this point, we’ve touched on how complex that is: how your vote counts (based on how the electoral college works), and the complications and calls for reform associated with redistricting. Zipcodes are shorthand for quality of life, social capital, or status, and so in that sense, jurisdiction – which sounds less than stimulating – is at the heart of the distribution of power among citizens.

It’s also a term that comes up frequently in the 2013 Shelby vs. Holder case which removed the requirement for preclearance under Section 4(b) of the Voting Rights Act of 1965. Read (and hear!) a breakdown of the majority ruling and the dissents on Oyez.org, “a multimedia archive devoted to making the Supreme Court of the United States accessible to everyone.”

K: Take your kid to vote with you!

From the New York Times, a reflection on how we learn to be civically engaged (or not) from our parents.

“‘Voting behavior is very much a habit,’ said Henry Brady, dean of the Goldman School of Public Policy at the University of California, Berkeley. ‘If you’ve had the behavior modeled in your home by your parents consistently voting, by political discussion, sometimes by participation, you start a habit formation and then when you become a little older you’ll feel it’s your duty and responsibility to register and vote.’ Civics courses are much less effective in transmitting that sense of duty and responsibility, he said.”

What’s your earliest civic memory?

L: Library

A tribute to libraries; often polling places, they offer communities and individuals centers for growing social and civic infrastructure every day. Eric Klinenberg writes of the power of libraries to enhance civic life in his new book:

“‘Here’s something I realized once I got to the library. At Starbucks, and at most businesses, really, the assumption is that you, the customer, are better for having this thing that you purchase, right? At the library, the assumption is you are better. You have it in you already. You just sort of need to be exposed to these things and provide yourself an education. The library assumes the best out of people. The services it provides are founded upon the assumption that if given the chance, people will improve themselves.'”

–Palaces for the People: How Social Infrastructure Can Help Fight Inequality, Polarization, and the Decline of Civic Life.

M: Midterms

Midterms are any national election that takes place without a presidential candidate. In recent years, voter turnout tends to be about 20% lower for a midterm than for a presidential election. However, we’ve recently seen some promising data on this previous point. In the 2018 midterm elections turnout soared from 37% to 50%, which was the highest turnout for a midterm election since 1914!

Midterm elections are incredibly consequential. From usa.gov, “Voters elect one-third of all U.S. senators and all 435 members of the U.S. House of Representatives during the midterms. Midterms determine which political party—Democratic or Republican—will control each chamber of Congress for the next two years. The party in control of either chamber is the party more likely to get its proposed legislation passed in that chamber. Proposed legislation must pass in both the House and the Senate for it to reach the president’s desk for approval.”

If you’re feeling like this information was in a government & economics class you must have slept through, we recommend the nonpartisan Civics 101: A Podcast, a production of New Hampshire Public Radio. 5 Things to Know About the Midterms is a 23 minute-long episode.

N: November 3, 2020

This year’s general election will be held on November 3rd, the first Tuesday in November. Curious about the history of how we got to such a specific date? Read more about that here. Tuesdays are a difficult time to take off work for many people, and there has recently been a movement to declare election day a national holiday.

O: Opportunity Gap

The term “opportunity gap” refers to the ways in which race, ethnicity, socioeconomic status, geography, and other factors contribute to or perpetuate lower educational aspirations, achievement, and attainment for certain groups of students (Glossary of Education Reform). The opportunity gap typically refers to the unequal factors that serve as “inputs” when it comes to student achievement–factors such as food security, family resources, and access to tutors are just a few that characterize the opportunity gap.

The gap is especially pronounced in Alabama when it comes to our rural communities and small towns. Many schools have had to consolidate in order to hold on to course offerings, but this means schools in rural communities are often closed, and students are required to spend a large portion of their schooldays just traveling to and from school. Outside of education, still, the gap persists in other facets of life. Many people are aware of “food deserts” in communities which lack access to healthy foods, and now there is a similar term for communities that have few opportunities to participate in public life–these are called civic deserts.

P: Primary Election

According to USA.gov, a primary election is “an election held to determine which of a party’s candidates will receive that party’s nomination and be their sole candidate later in the general election. In an open primary, all voters can vote for any candidate they prefer, regardless of the voter’s or candidate’s party affiliation. In a closed primary, voters can only vote for a candidate from the party that the voter belongs to.”

In 2017, Alabama changed the law regarding “cross-over voting” in party primaries, so that now the law states if you vote in a Republican primary, you are allowed to vote in the Republican run-off, if there is one, but you cannot vote in the Republican primary and then “cross-over” to vote in a Democratic run-off (if there was one)–and vice-versa, if you voted in the Democratic primary, then you can not then “cross-over” to vote in a Republican run-off, if there happened to be one.

Q: Qualifications

So who has the right to vote? To begin with a point of confusion, many legal scholars have observed that the Constitution does not, in fact, explicitly guarantee the right to vote (hence the 15th, 19th, and 26th Amendments, the Voting Rights Act, etc.). Politifact.com offers perspectives from both sides of the aisle in support of this observation. While it’s clear that the Constitution views voting as “so implicit as to be all but explicit,” the historical, social, and cultural dynamics at play in the history of U.S. voting demonstrate how, even today, it functions in a gray area between a right and a privilege.

Semantics aside, Usa.gov states that the rules are these: voters must be 18 or older, a U.S. citizen, and registered. States have their own laws regarding registration deadlines, residency requirements, voting by absentee ballot, voter identification laws, and felony disenfranchisement. There is no simple way to recount the hard-won protections in U.S. voting rights history against discrimination by age, sex, and race; however, you’ll find a list of recommended reading from DMC staff in various sections.

In summary, we’ve remembered while researching this article that voting issues are neither stagnant nor boring.

The past informs the present perhaps more than we realize (the reason we still vote on a Tuesday, for example), and the laws and movements we read about in history class have their counterparts today. The movement to lower the voting age to 16 is gaining traction; other examples include the ban the box movement, automatic voter registration, electronic voter registration, and the push to make voting a national holiday (see N). And, as we’ve laid out, concerns over voting discrimination still exist as well, from voter identification laws, to gerrymandering, to felony disenfranchisement, and more.

(This last point is not making a partisan statement, but rather is made in the spirit of understanding complicated issues for the sake of making more unified, representative, and effective decisions as a nation – staying informed and engaged if we wish to “keep our republic.” ) For this reason, we’ve included fact-checking resources under N.

R: Registration

Going deeper into the issue of automatic voter registration, we wondered whether that’s the only reason that so many Americans are still unregistered to vote. It turns out in 2016, the Pew Research Center found a number of differences (and similarities) between registered and unregistered voters. Their summary is below. (Emphasis and bullets added)

“The unregistered differ in many ways from those who vote frequently:

“They are less interested in politics, less engaged in civic activities, and more cynical about their ability to understand and influence government, but they are not appreciably different on these measures from individuals who are registered but rarely vote. However, the unregistered population is not entirely unengaged from civic life; some indicated that they would register, and that group also reported participating in community or political activities at rates similar to occasional and semifrequent voters.

“Further, more than 40 percent of the unregistered cared who would win the presidency in 2016, and some indicated that they could be motivated to register in the future, though many also feel that the voting process does not affect the way governing decisions are made. These findings suggest that opportunities exist to engage segments of the unregistered population, including through consistent outreach at motor vehicle agencies as required under the NVRA and public education campaigns designed to highlight the significance of individual voter participation to election outcomes and the connection between local policies and issues these citizens care about, such as those for which they volunteer in their communities. Less than 20 percent of this group has been asked to register by a state agency, and a substantial increase in that figure could help to improve registration rates and electoral participation among these disconnected citizens.”

S: Straight-Ticket Voting

Alabama is one of 7 states that allow straight-ticket voting, a practice that allows voters to effectively fill in their ballot for all Republicans or Democrats with one mark. Educate yourself on the ins and outs of straight-ticket voting on Ballotpedia. Even in states that don’t offer straight-ticket voting, it’s rare that Americans color outside their party lines. Most vote all one party or the other, according to Pew, and 2020 seems to be no different.

T: Transportation

Problems with transportation are one of the top ten reasons that registered voters didn’t participate in the 2016 presidential election. Lyft is one company offering free and discounted rides to the polls for those in need, but more often, this takes the form of local grassroots efforts.

If you need a ride to the polls or would like to offer a ride, visit carpoolvote.com. Or check your local Facebook networks.

U: Universities

Education is considered a significant predictor in whether, and how, people vote. FiveThirtyEight breaks down a recent statistical example and offers some nonpartisan interpretations of the data. Related, the Campaign for the Civic Mission of Schools is a movement working to strengthen how educational institutions teach for democracy. Read their 2011 report here, outlining challenges and solutions for providing a high-quality civics education to the United States’ upcoming generations.

V: Voting Rights Act

55 years ago, following the Civil Rights Movement, Congress passed the Voting Rights Act of 1965 outlawing voting discrimination at the local and state level against African-Americans. Such discrimination had continued relatively unchecked in many U.S. states, regardless of attempts to enforce the 15th Amendment (crippled by the Supreme Court in 1888), and despite more legislation in the 1950s and 60s. The National Archives observes that “because the Voting Rights Act of 1965 was the most significant statutory change in the relationship between the Federal and state governments in the area of voting since the Reconstruction era, it was immediately challenged in the courts. Between 1965 and 1969, the Supreme Court issued several key decisions upholding the constitutionality of the law.”

This history is alive and well in the South. The Atlantic outlines a recent development in the Voting Rights Act: Shelby vs. Holder. DMC staff recommends Diane McWhorter’s Carry Me Home as a lengthy but worthwhile read on the Civil Rights Movement in the South.

W: Women’s Suffrage

2020 marks the Centennial of the 19th amendment to the U.S. Constitution prohibiting the states and the federal government from denying the right to vote to citizens of the United States on the basis of sex. Find a brief history of women’s suffrage by state here, and some primary sources on women’s suffrage from the Library of Congress.

And don’t miss our new issue guide on Women’s Suffrage, which you can find here!

“X” Marks the Spot

From vote.org, simply enter your address into the search bar to find out where your polling place is.

Related, even those without a stable home address can still vote – at least in theory. People living in homeless shelters, on the streets, or in some form of temporary housing may still pursue the possibility of casting a vote. CityLab documents the particular difficulties of attempting to vote under such circumstances; here’s a related Ohio case on which the Supreme Court ruled June 2018 (and a local opinion piece here, explaining how homeless voters were affected as well as those who abstained to make a political statement).

Y: Youth Vote

The youth vote in America, coveted by politicians, is the subject of focus by the Center for Information and Research on Civic Learning and Engagement (CIRCLE). which resides at Tufts University’s Jonathan M. Tish

College of Civic Life. CIRCLE regularly puts out working papers, reports, data maps and sets, facts sheets, and more, all related to youth involvement in public life. For recent Alabama-specific research, read on.

Young people are more engaged than you might think, and early absentee/early vote numbers for the 2020 election are indicating record youth turnout!

Z: Zero-Sum Game

This is a turn-of-phrase from economics and game theory that is another way of saying “winner takes all”, which is exactly the way that elections work in the U.S. We don’t assign proportional representation in our electoral process, which means that whichever candidate wins, even by a single vote, that candidate “takes all” and the candidate that comes in second place receives nothing. There are some innovative changes taking place across the country, such as ranked-choice voting, that are trying to change this. For example, FairVote.org advocates for ranked-choice voting, stating that:

“In addition to indicating their first choice, voters in RCV elections may rank candidates second or third (or beyond) on the ballot. In the case that a voter’s higher-ranked candidates lose, the voter’s vote will count for their second-, third-, or later-ranked candidate. Unlike plurality systems, under RCV the contest for each voter’s vote is not a zero-sum game. In many instances, to be elected a candidate needs both the first choice rankings from his or her core of supporters as well as some lower rankings from other voters.”